A Quiet Crisis in Learning?

From the earliest days of storytelling by firelight to the modern age of instant connectivity, humanity has continually reinvented how we share and preserve knowledge. Each leap forward—from oral traditions to the written word, the printing press, and the internet—has reshaped not only how we learn but also what we value in the process of learning itself.

Now, with the rise of accessible AI tools, we face a new and unprecedented shift. AI doesn’t just deliver information; it processes, interprets, and even generates it for us. While this technology promises immense potential, it also challenges our traditional notions of intellectual effort and curiosity.

Is AI diminishing our drive to learn deeply, or can it become a partner in pushing the boundaries of human thought?

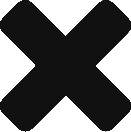

Gutenberg in his workshop – Credit Britannica

Early Lessons: Before the Printing Press

Long before Gutenberg’s time, books were painstakingly copied by hand—often by monks who spent their days in the scriptorium, hunched over manuscripts illuminated by flickering candlelight. Most of humanity had virtually no direct access to these texts. The circulation of knowledge was so limited that an individual might come across just a handful of manuscripts in a lifetime. Consequently, if you were one of the fortunate few granted the privilege to study a particular document, you had no choice but to memorize large portions of it. There was no guarantee you’d ever hold it in your hands again. You were your own library, and your mind was the only place to safeguard precious nuggets of insight.

This reality shaped not just how people learned but why they learned. Survival in the intellectual sense depended on one’s ability to internalize knowledge. The capacity to recite passages, to recall obscure references, or to manipulate complex theological and philosophical ideas was not merely an academic exercise; it was a form of cultural currency and a means to preserve collective wisdom. Oral traditions—epic poems, folklore, moral tales—were transmitted through memorization, reinforcing an ethic that placed a premium on one’s mental repository of facts, dates, and stories.

In that age, education was largely a matter of intensive internalization. A devout scholar might spend years memorizing the Bible or the Quran. Philosophical treatises, classical epics, and medical texts were likewise passed from teacher to student in a chain of near-photographic recollection, lest the knowledge be lost. When a single book might cost more than a year’s wages, you made every second with it count. And in doing so, you developed a fierce respect for memory.

The Printing Press and the First Wave of Democratized Knowledge

Everything changed in the 15th century. Gutenberg’s genius was in making movable type commercially and mechanically feasible on a large scale. What had once been the labor of many months—copying one book—could now be accomplished in days. Books started traveling beyond the confines of cloisters and palaces, winding up in the hands of merchants, teachers, and eventually, commoners. With this proliferation, literacy began to rise. New ideas, along with ancient ones once buried in scriptoria, ricocheted from city to city. The Renaissance was catalyzed, the Reformation was fueled, and a modern world began to emerge.

Amid this flurry of intellectual revitalization, a subtle shift occurred: the need for rote memorization eased. Where previously one might have needed to commit entire texts to memory for fear of never seeing them again, it was now conceivable to find a printed copy elsewhere. This accessibility was the printing press’s gift—but also its hidden peril. While reading became more common, the imperative to hold vast libraries in one’s head gradually lessened. And for many, that was an acceptable trade-off. As literacy became widespread, the argument went, more people could engage with knowledge, build upon it, and create new innovations. The net effect was overwhelmingly positive for society.

Access to the world’s information online

The Internet Revolution: A Second Great Leap

Centuries later, the distribution of knowledge reached its next logical extension in the form of digital technology. With the advent of the internet, knowledge was no longer just more accessible; it became ubiquitous. In the late 20th century, a curious mind could log onto an online database and, within a few clicks, locate the very texts that once took months of sea travel to procure. Modern search engines soon surpassed the dream of any ancient scholar: a near-instant gateway to an effectively infinite repository of ideas.

For educators, the internet was at once exhilarating and disconcerting. Students found themselves researching topics with a breadth and depth previously unimaginable. The entire canon of world literature was at their disposal, along with scientific papers, encyclopedias, news archives, and more. Yet, this oceanic abundance of data brought a new dilemma: Why memorize facts when they are always at your fingertips? Why delve into the nuances of a subject when you can skim the highlights from a well-crafted webpage?

Cognitive psychologists coined the phrase “cognitive offloading” to describe the reliance on external tools—like the internet—to store and retrieve knowledge that humans previously held internally. This offloading is by no means a modern invention: writing itself was an early form of it. But the internet magnified the effect exponentially. The skill of recall became less valuable. In an era of mass connectivity, the question was no longer how to remember a specific fact, but how to find and evaluate facts in a saturated information environment.

Enter Artificial Intelligence: The Current Wave

This brings us to AI—a technology that not only stores information but also analyzes and generates it. Modern large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and many others, do more than retrieve facts from a static library; they synthesize, interpret, and even originate content. Need a summary of Plato’s Republic? You can get it in seconds. Need an entire essay on the evolution of the printing press? AI can produce it—complete with references (sometimes hallucinated… but getting better all the time) —in the time it takes to brew a cup of coffee.

Here is the central concern: If a student can generate polished work with minimal effort, is there any longer an incentive to grapple with the underlying ideas themselves? Will the next generation of learners invest the time to wrestle with the works of Plato when they can simply ask for a prepackaged summary? The risk is that critical thinking, creativity, and the deeper joys of learning could wither as AI becomes an intellectual autopilot.

This challenge mirrors those in earlier historical junctures—only heightened. Just as the calculator reduced the cognitive load for arithmetic, and the internet made information retrieval practically effortless, AI now automates analysis and composition. But while it’s easy to tap a few buttons to perform a calculation, or click a website link, it’s another leap altogether to let a machine produce the very words and process of analysis we might once have formed ourselves. In short, we might be forfeiting not just memory, but engagement, reflection, and original thought.

Using AI from anywhere – Credit Averyanov

The Disincentive to Learn: A Modern Dilemma

Imagine a high school student assigned a paper on World War II. Before AI, they would research large volumes of information, synthesizing the data, connecting dots, and shaping a coherent argument. That process might have taken days, weeks or even months. Now, with a single query, an AI chatbot can spin out a well-structured essay replete with nuanced commentary. The student’s role in this scenario is minimal; they become an editor at best, a copy-and-paster at worst.

This convenience can easily disincentivize rigorous study. Why invest hours in reading multiple sources, verifying facts, and refining one’s thesis, when the machine has already done the heavy lifting? Why memorize historical figures and sequences of events if you can generate them on the fly with near-perfect accuracy?

It’s tempting to shrug and say that each generation adapts. When calculators became commonplace, there were dire predictions about the death of mental arithmetic. Yet, we adapted, emphasizing conceptual understanding over mechanical computation. However, the difference with AI is that it doesn’t merely automate basic functions; it can automate the higher-order tasks we once considered the essence of intellectual endeavor: composition, synthesis, creative exploration. By short-circuiting those processes, are we risking the development of the very faculties that lead to genuine innovation and personal growth?

What We Lose When We Let AI Do the Thinking

A crucial question arises: Does it matter if we lose the need to learn deeply? After all, the technology is here, and it’s going to stay. Why not outsource to AI the grunt work of analyzing historical events, writing essay drafts, or summarizing scientific breakthroughs?

The answer lies in understanding what deep learning actually confers. A robust educational journey is about more than transferring data into the brain; it’s about cultivating the capacity to make connections, to think critically, to empathize with perspectives across time and space, and to create something genuinely new. Moreover, it’s in the struggle—the intellectual wrestling with challenging ideas—that students often find their footing. They discover unexpected passions, develop resilience, and learn to articulate convictions that shape who they become as adults.

When AI steps in too early or too frequently, it can rob students of the raw materials necessary for those epiphanies. The illusions of comprehension that come from reading an AI-generated summary can be seductive. Yet deep understanding requires immersion, reflection, and, yes, sometimes confusion and frustration. The “aha” moment that results from clarifying a tough concept is the bedrock of genuine learning—a phenomenon that can’t be replicated by passively ingesting machine output.

Bridging the Gap: A Framework for Purpose-Driven Education

This leads us to the pivotal question: How do we harness AI’s immense power without sacrificing our humanity, our curiosity, and our motivation to learn? The answer lies in reimagining the purpose and methods of education for an era in which AI is a fact of life. Below are a few key areas I think we can focus on, ensuring that students grow, flourish, and find personal meaning in their pursuits—even as they navigate a world brimming with intelligent tools.

A. Nurturing Creativity and Critical Thinking

The new educational frontier isn’t just about transferring information; it’s about teaching students how to engage with information creatively and critically. Where AI automates rote tasks and even sophisticated analyses, human ingenuity can shine in asking questions that stretch beyond the constraints of what’s been programmed. Rather than simply testing whether students can replicate existing knowledge, we should reward the ability to pose novel hypotheses, to draw unexpected parallels, and to devise innovative solutions — likely working in collaboration with AI tools.

Project-based learning, interdisciplinary workshops, and real-world problem-solving can also cultivate the kind of thinking that can’t be easily replicated by a machine. Students might be asked to collaborate with AI on a given project but then defend their conclusions in a public forum—explaining the rationale behind their final product, pointing out where AI’s suggestions were integrated or rejected.

B. Cultivating Emotional Intelligence and Social Skills

AI, for all its power, lacks genuine emotion. It can mimic empathy through carefully designed responses, but it does not feel (as far as we know…). In a world where technology automates many tasks, the value of human-centered skills—empathy, communication, leadership, conflict resolution—will skyrocket. Schools can focus on group activities, peer-led discussions, and community service to help students develop emotional intelligence. This emphasis not only prepares them for evolving workplaces but also fosters healthier, more empathetic societies.

C. Instilling Lifelong Learning and Adaptability

The pace of technological change shows no sign of slowing. Today’s hot new tech can become obsolete in a matter of years—or even months. Traditional models of education often treat learning as a phase that ends at graduation, but that concept is increasingly outdated. Tomorrow’s workforce will require constant re-skilling. According to the 2025 Future of Jobs Report from the World Economic Forum, “On average, workers can expect that two-fifths (39%) of their existing skill sets will be transformed or become outdated over the 2025-2030 period.” Instilling a “lifelong learning” mindset means prioritizing curiosity, adaptability, and the willingness to embrace new challenges. Students should see education not as a chore but as an evolving journey. Encouraging them to explore interests outside their standard curriculum reinforces the idea that learning doesn’t end in the classroom.

D. Emphasizing Purpose and Well-Being

Amid the competitive push for STEM skills and AI literacy, it’s easy to overlook the deeper why of education: to help individuals lead fulfilling and healthy lives, contribute to their communities, and discover their unique calling. We should integrate opportunities for mindfulness, self-reflection, and community engagement that show students how their studies connect to a broader mission. Purpose-driven learning—tying academic work to real-world causes—offers a motivational framework for students, which will empower humanity to address the wide range of challenges we’ll face in the future. If the next generation understands why they are learning, they’ll be far more inclined to embrace AI as a tool rather than a crutch.

E. Leveraging AI as a Collaborative Tool

As with any technology, AI can be used passively or actively. A student might passively accept an AI’s solution, effectively substituting it for their own thinking. Or they might actively collaborate with the AI—treating it like a lab partner with strengths and weaknesses. The key is to train students not just to “use” AI but to evaluate it: checking its sources, understanding its limitations, and challenging it when needed. This approach transforms AI from a simplistic answer generator into a sophisticated instrument of learning, akin to a microscope or a 3D printer—an aid that can illuminate hidden details but ultimately relies on the human operator for context and purpose. Through this synergy, AI can serve as a stepping stone to deeper intellectual inquiry—freeing us from routine tasks so we can devote our time and effort to advanced problem-solving, creative thinking, and ethical decision-making.

In much the same way calculators initially seemed poised to replace mental math but ultimately pushed us toward higher-level concepts, AI’s real promise lies in its ability to expand our cognitive bandwidth. By offloading certain analytical or informational tasks, we gain the mental space to pursue more complex questions and discover new forms of innovation. It’s an opportunity to redefine what we focus on in our learning, aiming for deeper synthesis and creativity instead of rote knowledge.

A Renewed Perspective on Learning

The curious truth is that every “labor-saving” device throughout history has challenged us to recalibrate what it means to learn. AI is no exception. I believe the future won’t belong to those who rely on AI to do their thinking, any more than it belonged to those who skimmed the works of Shakespeare without putting in the work to truly understand them. It will belong to the curious few who see AI not as a shortcut around understanding, but as a springboard toward higher-order insights. The real danger isn’t that AI might kill our need to learn—it’s that we might forget to harness our oldest tool of all: our curiosity. Let’s not waste the opportunity to cultivate it.

P.S. — And yes, if you’re wondering, this essay was written in collaboration with AI 😉